:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Ise_grand_shrine_Naiku____-_panoramio_11-9dc722770a0749df802ae7b3c0cf5151.jpg)

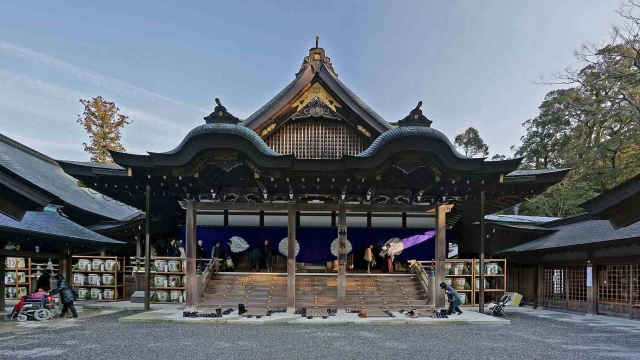

In the heart of Japan lies a spiritual landscape unlike any other, steeped in tradition and reverence. Shinto shrines are not merely structures; they are gateways to the divine, inviting visitors and locals alike to immerse themselves in the serene beauty of nature and the rich tapestry of cultural beliefs. Each shrine whispers stories of the kami, the spirits revered in Shintoism, connecting communities through rituals and celebrations that honor the ancient ways.

As one wanders through the enchanting atmosphere of these sacred sites, the gentle rustle of leaves and the soft sounds of flowing water create a harmonious backdrop for reflection and prayer. From majestic torii gates standing sentinel at the entrance to intricate wooden buildings adorned with symbols of nature, Shinto shrines in Japan capture the essence of the country’s spirituality and highlight the profound connection between the physical world and the ethereal realm. Exploring these shrines offers not only a glimpse into Japan’s past but also a chance to appreciate the present moment in a space where nature and divinity intertwine.

神社めぐり

History and Significance of Shinto Shrines

Shinto shrines in Japan trace their origins back to ancient times, with roots that intertwine deeply with the country’s cultural and spiritual history. The concept of kami, or spiritual beings, is central to Shintoism, which developed as a way for the Japanese people to connect with nature and the divine. Early Japanese society saw the worship of natural elements such as mountains, rivers, and trees, which gradually evolved into more organized expressions of reverence represented by shrines. The establishment of these sacred spaces marked a pivotal moment, as they became focal points for community gatherings, rituals, and the preservation of rich cultural traditions.

During the Heian period, the architecture and layout of Shinto shrines saw significant development. The influence of Buddhist practices led to changes in shrine design, resulting in the harmonious blend of architectural styles that can still be observed today. Notably, the practice of purification, particularly through water, became an essential aspect of approaching these holy places. Shrines typically feature torii gates, which symbolize the transition from the mundane to the sacred, further enhancing their significance in the spiritual landscape of Japan. As communities sought divine protection and blessings from kami, shrines transformed into vital centers of spirituality and social identity.

In modern Japan, Shinto shrines continue to play a crucial role, serving not only as places of worship but also as cultural heritage sites. They host annual festivals, ceremonies, and rituals that celebrate seasonal changes, community bonding, and ancestral reverence. The enduring presence of these shrines reflects the deep connection between the Japanese people and their historical roots, promoting a sense of continuity and belonging. Thus, Shinto shrines in Japan are more than mere structures; they are living embodiments of tradition, spirituality, and the ongoing relationship between humanity and the divine.

Architecture and Design Elements

Shinto shrines in Japan reflect a unique architectural style that is both functional and deeply symbolic. The simplicity and natural materials used in their construction are reminiscent of the Shinto belief in living harmoniously with nature. Traditional shrines are typically built using wood, often left unpainted to highlight the beauty of the grain. This approach not only honors the spiritual connection to the environment but also allows the structures to blend seamlessly with their surroundings, fostering a sense of tranquility.

Central to the design of Shinto shrines is the torii gate, an iconic symbol that marks the transition from the mundane to the sacred. Often painted bright orange or left in a natural state, these gates serve as a visual cue, inviting visitors to enter a space dedicated to the kami, or spirits. The layout of a shrine usually emphasizes a progression towards the main hall, or honden, with pathways lined by trees and stones that enhance the spiritual journey. This thoughtful arrangement encourages reflection and reverence as worshippers approach the sacred heart of the shrine.

Additionally, the roofs of Shinto shrines are noteworthy for their distinctive shapes, which vary depending on the region and the specific style. Common roof styles include the thatched and the gabled, often adorned with decorative elements such as shimekazari, or sacred hemp ropes. These roofs not only provide protection against the elements but also symbolize the connection between the earthly realm and the heavens. The careful attention to detail in both the aesthetic and spiritual aspects of Shinto shrine architecture creates a profound sense of place, inviting visitors to pause and appreciate the intricate relationship between humanity and the divine.

Rituals and Practices at Shrines

Visitors to Shinto shrines often engage in a series of rituals that reflect the deep-rooted customs and spirituality associated with these sacred spaces. One of the most common practices is purification, known as temizu, which involves washing one’s hands and mouth at a water basin before entering the shrine grounds. This ritual emphasizes the importance of cleanliness and respect key to Shinto beliefs. Participants typically use a ladle to pour water over their hands, cleanse their mouth, and then return the ladle to its resting place, symbolizing the transition from the mundane to the spiritual.

Upon entering the shrine, worshippers frequently offer prayers and make wishes. This is usually done at the main hall, where individuals toss a coin into the offering box, bow twice, clap their hands twice, and bow once more. This sequence of actions demonstrates sincerity and reverence towards the kami, the deities worshipped in Shinto. Some shrines also offer fortunes, known as omikuji, which can be drawn for guidance and insight regarding one’s future, lending a layer of personal connection to the shrine experience.

Festivals, or matsuri, play a significant role in the life of Shinto shrines, celebrating seasonal changes and honoring particular deities. These vibrant events often include processions, traditional music, and dance. During matsuri, the community comes together to celebrate, give thanks, and seek blessings for good harvests or protection from misfortune. Each shrine has its unique festivals, showcasing local traditions and deepening the relationship between the community and the kami, thus weaving the fabric of spiritual life in Japan.

The Role of Nature in Shinto Beliefs

Nature holds a central place in Shinto beliefs, reflecting the deep connection between the spiritual and the natural world. Shinto practitioners view the kami, or deities, as manifestations of natural forces and elements, residing in mountains, rivers, trees, and stones. This belief fosters a profound respect for nature, encouraging people to appreciate the beauty and sacredness of the environment around them. The landscape itself becomes a sacred space where the divine is present, and this connection reinforces the importance of living in harmony with the earth.

The architecture of Shinto shrines in Japan often emphasizes this relationship with nature. Many shrines are strategically located in picturesque settings, integrating seamlessly into their surroundings. The use of natural materials in shrine construction, such as wood and stone, further highlights this bond. Additionally, sacred sites are often marked by torii gates, symbolizing a transition from the mundane to the sacred, inviting visitors to enter a space that is imbued with spiritual significance and natural beauty.

Rituals and ceremonies in Shinto also reflect this reverence for nature. Offerings made at shrines often include rice, fruits, and other foods sourced from the land, symbolizing gratitude for the bounties provided by the earth. Seasonal festivals celebrate the changing of the seasons, honoring the kami that govern natural phenomena. Through these practices, Shinto reinforces the belief that humans are interconnected with nature, encouraging stewardship of the environment and a persistent recognition of the divine presence within it.